Connecting the Dots for Better Outcomes

The most vulnerable individuals in society often struggle with long-lasting, multi-faceted challenges such as mental illness, substance abuse, chronic health conditions, and homelessness. Individuals experiencing these difficulties tend to interact with public services and departments frequently, yet many communities struggle to identify them and meet their needs in meaningful and cost-effective ways.

At times of crisis, the first place to reach for help is through 911 to request emergency medical service or police intervention, but neither paramedics nor police officers are well-equipped to effectively address complex issues on-site. Typically, their only options are to transport the individual either to a hospital’s emergency department or jail. Neither of these outcomes are interventions that address long-term vulnerabilities or chronic underlying conditions. At the same time, these outcomes are an expensive and limited resources that incur societal and financial costs for both individuals and municipalities.

Innovative solutions have been developed to provide more holistic care options. For example, the University of Illinois health system recently launched an initiative to link some of its more frequent ER visitors with housing services in order to more directly and effectively improve the individual’s health. Our partners in Johnson County, Kansas, embedded mental health social workers as co-responders in several police and emergency medical departments in order to help prevent trips to hospitals and jail by providing alternate interventions and coordinating longer-term care.

Programs like these are great first steps, but they each address the issue from within their own limited view of the situation. The co-responders embedded within the police force aren’t aware of ambulance calls and hospital trips that don’t involve the police, so they might miss some critical opportunities for earlier, deeper intervention and improved care.

Our team — 2016 DSSG fellows Matt Bauman, Kate Boxer, Eddie Lin, and Erika Salomon with technical mentors Jen Helsby and Joe Walsh and project manager Lauren Haynes — worked with Johnson County, Kansas to prioritize proactive outreach for the co-responders as part of the Obama White House’s Data Driven Justice initiative. By bridging system silos between criminal justice, emergency medical transport and behavioral health, we formed a more complete picture of the needs of the community than is currently possible and developed a prototype early warning system for prioritized proactive outreach.

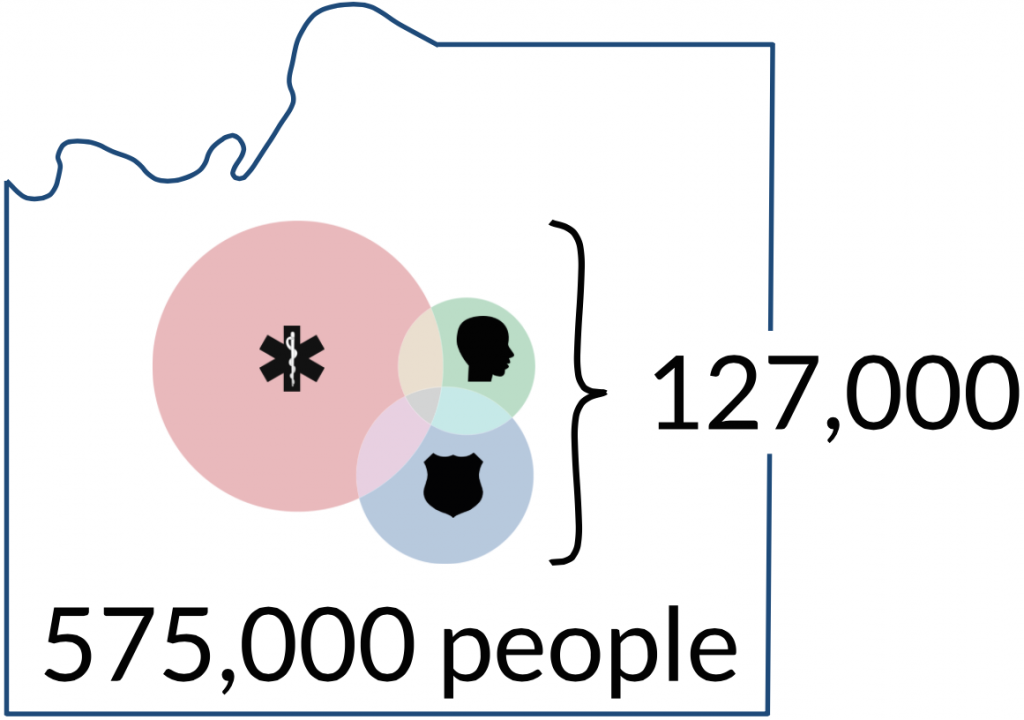

Johnson County is a mostly suburban region outside of Kansas City with approximately 575,000 residents. Of those, approximately one-fifth have interacted with emergency medical transport (red), the behavioral health system (green), or criminal justice (blue) within the last six years.

We’re focusing our efforts on individuals that interact with two or more of these public systems, as this population represents many of the individuals who are struggling with multiple vulnerabilities. There are over 12,000 people that have interacted with more than one of the county departments in those same six years.

During the summer, we had the privilege of riding alongside a team of Johnson County paramedics as they made a call. In the downtime that followed, we were able to talk about the project and how it might be beneficial to them and the community. One of the very first things they thought of was how this sort of proactive outreach might be able to help a case they vividly remembered. They had transported the same person to the ER for a drug overdose two years in a row on Valentine’s day and lamented that they simply aren’t able to do anything within their role to try and prevent it from happening again next year.

It was clear that the data points that appear as outliers to us are first names to them. They truly care for the folks they serve and would like to help more people achieve better outcomes, but are limited by the scope of their role and how they’re able to connect with them. Our project won’t be replacing this sort of very human identification and care, but it could help a different paramedic team responding the second time to recognize an actionable pattern. Connecting data across services might enable a proactive outreach and ideally prevent events such as this individual’s story from happening again.

Over the summer fellowship and subsequent months at the Center for Data Science and Public Policy, we developed an early warning system for individuals who had previously interacted with both mental health services and the criminal justice system and were at risk of re-entering jail in the following year. Based upon Johnson County’s anticipated intervention capacity, we focused on the top 200 individuals most at risk. We trained a machine learning model that used historical data from all three county services to rank individuals by their risk of re-entering jail in the subsequent year. The final year in the data set was held out to validate its performance.

Within that final year, approximately 10% of the 4100 individuals who had previously interacted with both mental health and the criminal justice system ended up going to jail. If a Johnson County co-responder were to try to enroll people into more comprehensive services at random, even the perfect intervention program would only prevent jail time in one out of every ten individuals.

Of course, it’s unlikely that the co-responder would actually reach out entirely at random. These are smart people; they’d look for a few key risk factors and focus their outreach towards individuals they deem at elevated risk based upon these heuristics. We modeled this behavior with 1- and 2- deep decision trees, which simply asked if an individual had been to jail in the previous year, and if they had, the average time between interactions with any of the public services was less than 611 days. By focusing on the highest risk individuals with this more measured approach, the co-responders would have a 40% chance at identifying individuals who may otherwise end up going to jail.

Our final model was a random forest classifier composed of 100 decision trees with as many as 20 levels within each tree (with a minimum of 5 samples at split and square root maximum features used at each split). It incorporated 252 unique features generated from all three public services. With this more advanced model, we were able to identify the top 200 at risk individuals with a 51% accuracy. This means that every other proactive outreach attempt would have the chance to reduce or eliminate jail time.

Just within these 200 individuals, the total jail time is substantial; all together, they combined for nearly 18 years of jail time. This incarceration is an enormous burden on them, their families, their workplaces, and the community at large. The chance to avoid a jail visit through a prioritized outreach program is extremely valuable.

This model represents a significant avenue for Johnson County to implement an intervention program where human insights into the ongoing struggles of individuals can provide substantive help in getting people connected with comprehensive care, counseling, or treatment. As a first step, Johnson County is evaluating the lists of individuals our model deemed highest risk. This process involves discussions with stakeholders, including mental health center employees, about the usefulness of the lists and the potential for interventions.

These interventions don’t have to be complex and expensive. They could include proactive follow-ups by mental health caseworkers with individuals identified as at risk and who have been out of contact for a substantial amount of time (e.g., over one year) in order to maintain accurate contact information and reassess current needs. Given that the median time since last contact for the at-risk population was over eight months longer than the rest of the population, this simple step alone could have a significant impact in reconnecting individuals at risk to mental health services.

This project is showing great promise for Johnson County to address a very real need in their community. They will have the chance to divert up to 18 years worth of jail time — time that can instead be spent with families and at work. Instead of paying for that incarceration, Johnson County can reinvest in their community and directly improve the lives of its residents.

Moreover, this same framework can be extended to other populations in need within Johnson County and across the nation. We have open-sourced this prototype system on GitHub and have written a technical report with more details that we’ve submitted for peer review. We look forward to extending it to other populations and other jurisdictions through participation in the National Association of Counties Data Driven Justice Initiative.